Disastrous Fire at Cippenham Green, 1908

A century ago, house fires were much more common than they are today. Open hearths and naked-flame lighting created opportunity for accidental fires to start and the higher flammability of furnishings meant that they could take hold with rapidity. The fire brigades were much less well equipped and could take hours rather than minutes to arrive on scene. Aside from the loss of life caused, it is sad that many fine historic buildings would otherwise be around today if it hadn’t been for the high frequency of house fires.

In Cippenham, the year of 1908 had got off to a very cold beginning. Shortly after new year’s day the sluice on the stream had been opened to allow the lower parts of the north side of the green to flood and then freeze. On Sunday 12th January, ice skating on the green had once again been enjoyed by both children and adults. Cippenham village green could hardly have looked more picturesque with the grass and trees coated in a thick layer of glistening frost that showed no sign of thawing. No doubt the air was crisp but with an acridity from the quantities of coal and wood being burned in every hearth. Villagers retired that night in temperatures of minus eight Celsius (or 18 degrees Fahrenheit as they would have recognised). In the small hours of Monday, a house-fire started in the centre cottage of a row of seven in Cippenham Green. The fire would spread through the whole row, gutting three of the the cottages and severely damaging two others. It would leave one person fatally injured and another seriously burned. Six families would be left homeless. The story of the fire gained national attention and this account of the events of that night has been put together from some of the many newspaper reports made at the time.

The alarm was first raised by Mr George Weatherill who lived opposite the row of cottages. He had awoken at 2:45 am to see a bright orange light and initially thought that someone had entered the bedroom in which he and his wife were sleeping. He realised, however, that the light was outside and coming from the cottage belonging to Mrs Ellis (60). He ran outdoors wearing only his shirt in order to rouse the occupants. Some short time before, Mrs Ellis had been woken by barking dogs and heard what sounded to her like the crackling sound of burning wood. She woke her son, Garforth (28), telling him she thought there might be a fire downstairs. Mrs Ellis then went down the stairs and Garforth followed her. When she opened the door to the sitting room she was engulfed and knocked down by a blaze of flame. Her son got her up and tried to get them both to the back door but they were beaten back by the flames and severely burned. Garforth then carried his mother upstairs and got her out through a window onto the sloping roof of the wash-house. From there they jumped to the garden. By coincidence, their cottage was the only one to have a wash-house. Once on the ground Garforth noticed that his and his mother’s clothing was on fire.

The occupants of the other cottages had been roused by this time. Mrs Ellis and her son were sheltered in Mr Weatherill’s cottage to await the attendance of the doctor. Mr Weatherill hurriedly put on trousers and then ran into Slough with another man named Collier, whereupon they raised the Slough fire brigade and Dr Fraser. Meanwhile, two dogs and several birds in the Ellis house were burned to death and the fire quickly spread to the other cottages. It seemed likely that the whole block would be destroyed. The occupants were all out on the road, still in their night clothes and in a state of panic-stricken frenzy.

The block of seven cottages that caught fire are shaded in red on this OS map updated 11 years before the fire. Note the wash-house on the centre cottage belonging to Mrs Ellis.

In this era, fire engines were horse drawn. Burnham fire brigade’s engine was a manual type where the water was pumped by hand. Slough fire brigade possessed a more sophisticated type of engine where the water was pumped by steam power. The Burnham fire brigade’s engine arrived on the scene at around 5 am by which time all seven cottages were well alight. The Slough fire brigade with their streamer, arrived shortly after at 5:11. The village pond was an obvious nearby source for water. Unfortunately, however, the ice on the pond was so thick that when the Burnham engine was backed onto it the ice showed no sign of breaking. Attention was then turned to the stream which ran behind the cottages. The extreme cold was a great hindrance to the fire fighters. The water from their hoses froze in large icicles on the cottages and their uniforms froze stiff.

When the doctor arrived on the scene, he sent Mrs Ellis and her son by cab to the Windsor Royal Infirmary. Nurse Worthington of Burnham who had rendered first aid, went with them. This was at 7 am by which time the fire brigade had the fire under control. Mr Weatherill permitted his sheds to be used to hold a great deal of property and he accommodated around a dozen of the residents in his house. Only one cottage escaped with minor damage. This was the home of the Colliers. The fire brigades left at around 9:30 to cheers and applause (by this time a considerable crowd had gathered).

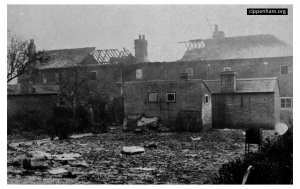

Mrs Ellis died of her injuries two days after the fire. Garforth spent many days in the infirmary. The other victims were put up in the church institute (the tin church) and a number of charitable villagers prepared them regular meals. Various events were organised to raise funds for the unfortunates. The burnt out cottages briefly became a tourist attraction and a fair sum of money was collected from those that came to view them.

The cause of the fire was never established but the Ellis cottage was heated by an open hearth which had been left embering when Garforth went to bed. At the inquest, Garforth (a pipe smoker) couldn’t say for sure that he had extinguished the paraffin lantern before he retired. The cottages were old, dating back at least as far as the 1840s. They were in the ownership of one private landlord, and were fully insured. They were eventually restored. The cottages were finally demolished some time after 1962.

Sources

- South Bucks Standard, 17 January 1908 p3, 24 January p8, 07 February 1908 p8

- Bucks Herald, 25 January 1908 p7

- Western Daily Press, 15 January 1908 p6

Leave a Reply