The Slough Bomb Mystery

Of the many secret files of World War Two that have been declassified, only one contains the word ‘mystery’ in its title. The event that confounded the British War Cabinet and the high-command of the RAF was termed the Slough Bomb Mystery and it took place on 13 July 1940.

Over the ten months since the war began there had been little activity over mainland Britain from the Luftwaffe. This was so contrary to public expectations reinforced by extensive air-raid preparations that it had become known as the Phoney War. Over the preceding six weeks, however, the fact that Britain had entered a desperate struggle for survival had been brought firmly home with the fall of France, the Dunkirk evacuation and the grim undertones of Churchill’s speeches to the nation.

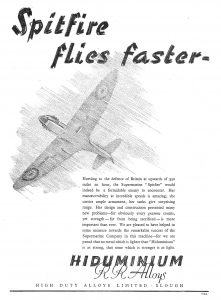

Only a small few factories in Britain had been bombed and Slough Trading Estate hadn’t yet suffered an attack. If the Luftwaffe had decided at this time to strike on one particular factory on the Trading Estate then it couldn’t have selected better than High Duty Alloys Ltd. Situated at 80 Buckingham Avenue the factory produced a range of specialised alloys named Hiduminium which had been developed by Rolls-Royce for use in aero-engines. All RAF planes had pistons made from forged Hiduminium and supply was considered so vital that a shadow factory was being set up in a remote part of Cumbria. The Slough factory was working 24/7 to meet the needs of the aircraft manufacturers.

Returning to 13 July, at 11:10 pm a single large explosion rocked High Duty Alloys, killing (at least) three workers and injuring 30 others. Although there was no doubt that a bomb was responsible for the explosion, the peculiar thing was that no aircraft activity had been detected over Slough. If the bomb had been dropped from an aeroplane then it must have been flying at very high altitude not to have been heard by the aircraft spotters situated all around the Trading Estate. For an aircraft flying at such an altitude (and in darkness) just managing to hit the Trading Estate with a bomb would have a been largely a feat of luck. To have caused a direct hit on High Duty Alloys seemed implausible. The dropping of just a single bomb was also unusual.

The War Cabinet request an explanation

The government’s Chief Inspector of Explosives, Colonel Thomas, was dispatched to the site the next day to determine whether the bomb, instead of being dropped, could have been planted as an act of sabotage. Thomas examined the deep crater going through the concrete floor of the factory. Embedded in the soil at the bottom were part of a metal grid previously set into the floor and also parts of the overhead crane. From this, he concluded that a bomb falling from above had carried these parts down with it and sabotage could therfore be ruled out.

Sir Hugh Dowding, the Head of Fighter Command received a memo on 19 July informing him that the Chief of Air Staff had been requested by the War Cabinet to investigate and report to them on the circumstances of the Slough bomb. The memo went on: “It is obviously unsatisfactory that bombs should drop in this mysterious way and I write to ask you if you could let me have some explanation of how this might happen, for the information of the War Cabinet”. The expectation of Britain’s elaborate air intelligence system was that it should be impossible for enemy aircraft to operate undetected. If the Slough bomb had been dropped by an aircraft, then a serious failure of the system had occurred.

Incident is forgotten

Dowding reported back on 23rd July. After outlining the known details he concluded that either the bomb had not been dropped by an aircraft, or that if it had, the aircraft had been flying so high as to be beyond the range of detection by sound. He rounded off with ‘Personally, I am inclined to suspect the IRA’. This might have seemed an odd statement, but given the great unlikelihood of a bomb having dropped so fortuitously, perhaps it seemed less improbable that Col. Thomas’s conclusion was incorrect. The IRA had commenced a vigorous campaign of attacks on British soil in 1939 named the s-plan and High Duty Alloys would certainly have been eligible as a target. What might have appeared to be a temporary hiatus of the s-plan during the previous weeks, however, proved to have been a complete fizzle out, much decreasing the likelihood that the IRA might have been to blame.

In consideration that the bomb might have come from an aircraft flying at very high altitude, Dowding had mentioned two X-raids over the sea which would have had time to reach Slough at 23:05 (X-raid was the term used for unidentified aircraft detected by radar). Shortly after Dowding’s report, further corroboration of aircraft activity emerged in the form of a former Observer Corps officer, Colonel G.C.K. Clewes who was staying near Slough that night. While outside, he heard an aeroplane pass overhead twice at what he thought was great height. He had no difficulty in identifying from its sound that it was German.

Matters effectively ended there. The War Cabinet never pressed for any further explanation. The Battle of Britain had begun and the RAF would soon be stretched to breaking point. The Assistant Chief of the Air Staff concluded “The bomb which fell on the works at Slough bids fair to become a mystery of the air comparable only to that of the famous Marie Celeste at sea!”. The file remained classified and only became available to the public in 1971, by which time the incident would probably have been far from the minds of those who originally knew of it.

Some new light

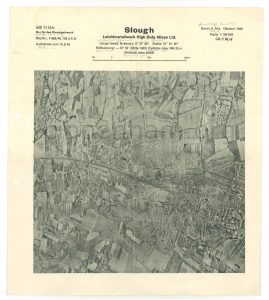

In its researches, we at ‘Old Curiosities’ recently came across a very interesting artifact which may relate to The Slough Bomb Mystery. Displayed opposite is a reconnaissance photograph of Slough Trading Estate taken by the Luftwaffe on 15th August 1940. The title is obviously curious as it explicitly names High Duty Alloys Ltd. (HDA) rather than the Trading Estate. It appears to confirm that HDA was considered the target of highest importance on the Trading Estate. The date is interesting, taken on 15 August 1940 – just over a month after the bomb. Was the purpose of this photograph to assist a future raid, or to assess the damage from the previous bomb? It seems strange that HDA is not specifically marked in any way on the image. It is interesting to note how well the document was produced as if it were for distribution in volume.

Perhaps this document was one of many similar target images that were distributed to bombing groups. If a group was assigned a particular target to raid, mission-planners would already have appropriate photographs to hand. These photographs would then be annotated by hand according to the particular details of the attack. This seems to fit with a similar Luftwaffe reconnaissance image that can be found online. In this case, the photograph is of Glasgow-Govan. Although the image is of the Clyde Shipyard and Docks, in a similar manner to the Slough image, it is subtitled Harland & Wolff Ltd. There are various annotations added by hand in red. This includes a single building marked with a solid outline which is, interestingly enough, the Harland and Wolff foundry. It would therefore seem likely that foundries in general were prime targets for the Luftwaffe.

It could have been a guided weapon

We were led to wonder if it was possible that the Luftwaffe may have employed some form of targeting using infra-red light. As foundries produce a great deal of heat, they would surely stand out very clearly if they could be viewed in the infra-red part of the spectrum. A so-called ‘glide bomb’ equipped with sensors that reacted to infra-red light would be able to self-steer towards a heat-producing target. The Germans certainly did develop and use various forms of glide-bomb, but they only came into service later in the war. The Fritz X for instance was an anti-shipping bomb which entered service in 1943 and was guided to its target by radio control from the plane which dropped it. A self-steering bomb using infra-red sensors might have been easier to develop. Germany had certainly recognised the great potential of passive infra-red homing for weapon delivery. It is possible that by July 1940, the technology existed to create a specialised ‘homing bomb’ for deployment against targets which generate substantial heat such as foundries and power stations.

If any evidence could be located to confirm that this is what happened the Slough bomb mystery would finally be solved. If such a weapon had been used against High Duty Alloys it would be mildly ironic. The existence of the infra-red form of light was discovered in Slough by its most famous resident, the English astronomer (of German origin), Sir William Herschel.

A fascinating story. I think there may be another explanation for how the bomb came to be delivered so accurately. In 1940, the Germans were operating a system to guide a bomber to its target using intersecting radio beams. Apparently, it was incredibly accurate and bombs could be dropped to reliably hit within 100 yards of their target. The system was so vulnerable to countermeasures that the Germans gave up on it in 1941 (along with precision bombing). When the British first detected the radio beams they found that they were converging on the Rolls Royce Merlin engine factory in Derby. Look up “Battle of the Beams” on Wikipedia for more information.

Jim White

My father told me that one night Lord Hawhaw came on the radio and said to the people of Slough that he hoped they’d got their Horlicks in as the factory would be gone in the morning. That night the bombers came en mass for the trading estate. The boffins from nearby Ditton Park had worked out how to create a signal to deflect where the German navigation beams crossed without the pilots realising. That night all the bombs fell harmlessly in the countryside. Shame that now the developers might do the job that the bombers couldn’t.

I remember my mother telling me about Lord Haw-Haw’s reference to Horlicks.

Does anybody have the actual date of this broadcast? I would like to link it to a family event that happened in 1940.

I have been researching the 1940 incident for almost 10 years now. I am currently writing a book about it and, as an oral historian I am especially interested in people’s memories of the explosion. Like many people I grew up with the story which, I have discovered is inextricably linked to my family history. Over the last ten years I have spoken to the families of those affected by it. If any readers have any memories of that fateful night then it would be wonderful to hear from you.

I am researching my family history and I have reason to believe that the one death that night was that of my great great uncle.

My Husband as a 12 year old boy, remembers. 1st bomb at HDA. 2nd at Farnham Royal Church Graveyard, uncovering Tommy Farr’s grave, TF was a well known boxer. 3rd at Stoke Pages Golf Club. They were called ‘stick bombs’.

We both use to hear the drop hammer all night long , used at HDA. Also the smoke screens, making. a ghastly fog. They gave off a sooty residue which made every thing black. Washing definitely couldn’t be hung out , wasn’t allowed at night as a signal to the enemy. Our shoes used to be caked in the tar, ears and noses dirty from the soot. Windows sills also covered in the silt. Don’t Touch was the cry !!!

From EJ White ( mrs)

Thank you for sharing your very interesting memories. Does your husband recall that the three bombs fell on the same night? This would be a highly significant detail we haven’t heard before.

I wonder if it could have actually been a relative or associate of Tommy Farr’s whose grave was disturbed by a bomb, as Tommy Farr lived for a long time after the war. Tommy Farr was a Welsh boxer who became British and Empire heavyweight champion. He could have become world champion having narrowly been defeated by Joe Louis. Farr was known as the “Tonypandy Terror”. Many Welsh from the Tonypandy region settled in Slough in the thirties. Tommy Farr was based in Slough in the mid-thirties and trained at The Dolphin. Naturally, he had a large local following.

It’s very nice to hear people’s memories of the event and of the time. The bomb that fell on the churchyard was in October 1940 and disturbed the graves of the men killed in the July explosion. None of the Farr family died thankfully. All the men in Farnham Royal are buried next to each other. Another man is buried in Datchet. The stories behind the men’s names are heart-breaking and those families I have spoken to for my research, talk of the pain and anger still being present today.

The RAOB held memorial services for the men during the 1940’s at their gravesides – they were determined the men would not be forgotten.

My dad worked at HDA from pre war to about 1960 and we lived in Westcroft .

Dad told of a bomb hitting St Marys gravyard as he rode his bike from work and he went past Crofthill to have a look.

He said the row of HDA Graves had been hit.

There was a Silvia Farr that went to Godolphin. Tommy Farr’s niece I think. I did not know her personally but I certainly knew of her.

Bomb was dropped on Farnham rd. By HD.and Bestobell Blew out windows in area.I lived nearby on Northampton Ave.

i lived IN KING EDWARD ST CHALVEY ALL DURING THE WAR WE HAD SMOKE STACK OUT SIDE OUR HOUSE LATER ON WE HAD A PIG BIN PLUSE A GAS LIGHT LAMP POST A MAN ON BIKE WITH HIS LADDER ON HIS SHOLDER WOULD LIGHT ITON BAD NIGHTS SLEPT IN THE SHELTER

My uncle George Nicholas worked at HDA during the war and had been in the foundry minutes before the explosion. He was adamant that there was no bomber and that it was sabotage. He also said that there were more people killed than claimed, At least one was in a vat of liquid metal and there was a head in the rafters.

We lived in Bedford Avenue on the estate. The old fire station.

HDA hada lot more going on there than people knew. There was a railway track throuh the estate that carried coal and munitions.

My dad was blow of a roof on the estate while replacing tiles. He was 14 at the time. My grandmother told me that there were quite a few bombs and doodles that hit the estate during the war. Hence all the anti aircraft guns on each ofthe bridges across the main railway. I played in the gun emplacements as a boy.

The database of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission contains the following two records of civilian deaths on 13 July 1940.

CRAGGS, JOHN age 28 of 77 Bryant Avenue. Son of Mr. and Mrs. F. Craggs, of 6 Gillow Street, Cornsay Colliery, Co. Durham; husband of Hazel G. Craggs. Died at 89 Buckingham Avenue.

WATTS, FREDERICK age 29 Sheffield Road, Farnham Road, Slough. Died at 89 Buckingham Avenue.

If you are related to one of these people, or someone else who was at HDA on the night of the bomb then we would be interested to hear from you.

Hello,

An interesting article, thank you. Do you know who/what caused of the fire that destroyed Rheostatic on the Trading Estate in 1939?

Thank you

Janet

‘Ironically, the first real damage to a critical industrial target in Britain was by an RAF Blenheim bomber, not a German bomber; on 14th July a Blenheim returning from an aborted raid accidentally dropped a bomb on the High Duty Alloys plant in Slough’

From ‘We march against England’ by Robert Forczyk, Osprey press.

Just rotten luck then…

I lived in Beechwood Gardens behind the Granada cinema through the war. We had 2 underground air raid shelters on the ‘green’ the large grassed area in the estate still there. My recollection is that there were just two bombs that caused serious damage in Slough. The HDA one and another that hit a house in a terraced row on the Bath Road close to the Town Hall. The house was destroyed but there was an upright piano up against the wall on the first floor. It was not removed for years. Opposite I remember the iron railings being cut away from Salt Hill playing fields as we were short of iron. Another memory was collecting the tin foil the German aircraft dropped to fool our radar

I have always wondered about an explosion in Cippenham during 1940s which blew out the window in St. Andrew’s church above the altar. My mum was the church cleaner and was called out to clean up the mess. I remember going with her to help. There was glass everywhere, inside and out. All over the altar. I have never found out what caused the local explosion. I was born in 1941 so it could have been any time after 1945.

I was born in Bower Way 1942. I can remember being taken into the living room one morning and looking up there was no ceiling just the light swinging from 2 of its 3 chains. I do not know the year, but it must have about 1943.

My sisters pillow had a large shard of glass in it.

My father was an inspector at H D A and both my brothers were apprentices the during the war