The strange tail of the Chalvey Stabmonk

Few people today will have heard of the bizarre ‘Stabmonk’ ceremony that took place annually on Whit Monday in Chalvey where a plaster-cast effigy of a monkey was given a mock funeral and burial. The first printed reference to the Stabmonk is from 1865 [1] but it may have already been around for many years by then. The ceremony continued to be held until the early 1960s. It’s said to commemorate an incident in which a real monkey was brutally slain in Chalvey Grove. In this era a monkey would have been a rare and unusual thing to encounter.

Origin of a peculiar ceremony

The traditional story [2] goes that there was once an enclave of Italian travelers living around Thames Street in Windsor, one of whom made his living as a street entertainer by grinding an organ. As he played, a cute little monkey dressed in a smart red jacket would dance and collect coins. One Sunday in spring, the organ grinder went to ply his trade in Chalvey Grove, hoping to make a few coppers. As he played, a crowd of children gathered, but they began to tease the monkey. The monkey retaliated by biting the finger of one of the children, who ran home. The child’s father, a truculent drunkard, ran to where the organ grinder was performing and stabbed the monkey to death.

The aggrieved organ grinder greatly bewailed the loss of his livelihood and local people took pity and decided to organise a collection to buy a replacement monkey. Much more money was raised than necessary and so the additional proceeds were used to hold a funeral ceremony for the monkey. The little bloodied and dusty corpse was taken in a solemn procession around the village, before being buried. A somewhat less sepulchral wake followed with free beer provided for the mourners.

Later that year, the villagers of Chalvey began to discuss how they might celebrate the holiday of Whit Monday. They decided that as such a good time was had at the monkey funeral, the whole occasion ought to be repeated. To solve the problem of not having a corpse, a skilled plaster-worker was procured to create a cast from the cadaver, which on exhumation was found to be sufficiently intact for the purpose. A collection was again made, but this time the entire proceeds were spent on the victuals.

Although the consumption of beer formed a major part of the proceedings, the ceremony became quite elaborate over the years. One feature was the ‘election’ of the Stabmonk mayor; this being the first man to become drunk enough to fall into Chalvey brook (usually with assistance). The ‘Mayor of Chalvey’ would retain his title until the following year. Attesting to the ceremony being a rowdy affair, on one occasion the local policeman who had come to keep an eye on the event got pushed into the brook. The policeman took this in good spirit and declared himself to be the new mayor [3].

Speculation on an inner story

Traditional games formed part of the festivities and the men of Chalvey competed with the men of Cippenham in quoits, shotput and a tug-o-war which took place over Chalvey brook. The funeral procession went around the village led by pallbearers in top hats and tails who transported the plaster Stabmonk on a small carriage under a tasselled canopy. Next came the Chalvey banner which celebrated Chalvey’s ‘industries’ – taking in washing, making babies, drinking beer and working in the treacle mines. The latter was a euphemism for certain activities that took place in the quagmires that surrounded the village. Behind the banner came the ‘official’ mourners. These included the previous year’s Stabmonk mayor who led two boys on chains with blackened faces and who danced like monkeys, a mounted highwayman and various others. The funeral procession ended in Chalvey Grove where a grave had been prepared. The burial itself was a private affair, closed off from all except for a select few who were all Chalvey men born and bred. It is recorded that the police in the 19th century had tried to prevent this part of the ceremony from taking place [1]. It has been said that the reason for this was that the burial ritual involved some form of obscenity, which brings us to the subject of the monkey’s tail.

The shape of the Stabmonk’s tail was changed in 1934 after the original one was (apparently) accidentally snapped off. Prior to this, the tail, which protrudes upwards between the legs was much shorter and bulbous at the end, giving it a distinctly phallic appearance. Before 1934, the Stabmonk’s modesty was preserved during the funeral procession by placement of a green cloth cut in the shape of a fig leaf. For the burial ritual, the cloth was removed. Today, the significance of these details is lost but it can be speculated upon. There were certainly versions of the story in which the monkey had escaped from the crowd and entered a bedroom through a window. A possibility is that its death came about through being caught in the performance of some lewd act. Those who were in the know could take secret delight in the vulgarity of the actual story while the bitten finger was the sanitised version that could safely be told to everyone else. In the 1930’s, however, the ceremony was attracting interest from wider afield and was being attended by increasingly important dignitaries, including the Aga Khan. Perhaps difficult questions were being asked and a decision was made to further conceal the true story and the tail was modified accordingly.

A connection to witchcraft

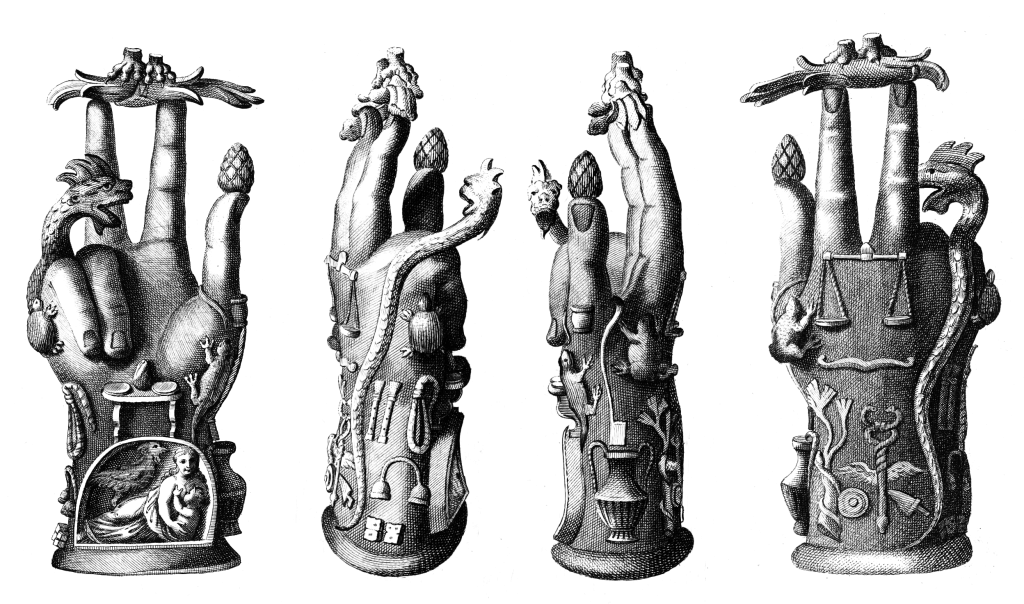

Witchcraft – A hereditary tradition, a book published in 2017 [4] offers an alternative perspective on the Stabmonk ceremony: that it was in fact organised by a local witchcraft cult which persists to the present day. Although the members of this secret and incredibly ancient sect refer to themselves as Stabmonks, the name is not connected to the murder of a monkey, this being a myth created to disguise the practice of their mystery rites. In the lore of the cult, the name Stabmonk is a derivation of Sabazios Mone. Sabazios is a deity whose worship originated among the Thracian tribes, an Indo-European Bronze-Age culture that inhabited the Balkan Peninsula before 1200 BC. The second word Mone, is an archaic British word meaning Lord. Elements of the cult of Sabazios influenced the Greek and Roman pantheons, but the specific veneration of this deity also took place in Greece and spread through the Roman Empire. As with other mystery cults, it was practiced in secrecy even before the suppression of them by the Christian Roman Empire began in the 4th Century. The most significant archeological evidence for the ubiquity of the Sabazios cult is the widespread distribution of artefacts known has the Hand of Sabazios. This is a hollow-bronze life-size casting of a hand with the index, middle finger and thumb raised. Various objects are depicted on the hand including reptiles and a pine cone.

The Stabmonks believe that their cult was brought to Britain in 1103 BC by a band of warriors who had been displaced by the fall of Troy. They were led by an individual named Brutus who went on to found London as his seat of power. It is strange that no archaeological or historical trace of a cult that has been practiced in Britain for three millennia has been found, but perhaps the story of the origin is allegorical, or worship was localised to Chalvey. It is a premise of the book that such lore and beliefs can be handed down in an hereditary manner, leaving no trace in recorded history. Strict secrecy was necessary in order to avoid persecution under the witchcraft laws which were only repealed in 1951. To this end, the sect has operated on similar lines to other clandestine organisations, with each initiate only knowing the identity of a small few others. It was also necessary that nothing should ever be written down concerning the sect and its practices that could be used to identify or convict followers.

According to the Stabmonks, the Chalvey ceremony had been held since antiquity. It would have originally taken place on May Day, which was once the pagan feast of Beltane marking the start of summer. The various aspects of the ceremony have pagan significance although most of the participants would have been unaware of this. The election of the Stabmonk mayor is one example. In the time of the Celts there was a tradition that under some circumstances a religious sacrifice of the life of the local king or chieftain was required. In time, this was superseded by a belief that a lesser individual could be anointed as a proxy king who could be subsequently sacrificed in the place of the real king. A useless individual such as the village drunk would be selected. He would have some fixed period of ‘reign’ during which he would enjoy certain privileges before the time of his sacrifice arrived. Although this sounds similar to the film “The Wicker Man”, a difference is that the proxy king would probably have been a willing victim. The book goes on to ascribe significances to other elements of the Stabmonk ceremony. An alternative explanation for the simian form of the plaster Stabmonk is not offered by the book, leaving one to conclude that its existence was merely to reinforce the myth of the monkey stabbing, rather than being an effigy or idol of the god Sabazios.

Further research

The lockdown hindered our research considerably but we were able to make some progress. The suggestion that the Stabmonk had an ancient origin first appeared in an article published in 1964, titled “The True History of the Stab Monkey” [3,4]. The late author, Michael HH Bayley was a chartered architect and an authority on local customs. Much about the Stabmonk had been related to him by his father and grandfather, who was brother in-law to Ernest Headington, the proprietor of Cippenham Court Farm. The article was published in the bulletin of the Middle Thames Archaeological and Historical Society (MTAHS), and according to Fraser’s History of Slough [3] it attempted to trace the origin to the religious rites of Dionysus (i.e. to ancient Greece). The traditions of Dionysus and Sabazios are known to have been closely related, and in fact, the pine cone which is always present on the thumb of the Hand of Sabazios is a symbol of Dionysus.

In our attempt to access The True History of the Stab Monkey, we made contact with MTAHS, but as soon as we asked about the article it went silent and we got no further replies to our communications. We also contacted Mr Dathen, the author of Witchcraft (which cites the article), but he was unable to assist us, having only been granted access under supervision by a source he didn’t wish to divulge. The closest we came to success was via a former acquaintance of Mr Bailey’s, who supplied us with the draft of an updated article from 1992, titled “The Chalvey Stab Monk” [2]. Although this is based on the earlier article, it omits the more esoteric details. In this respect, some of the handwritten edits are intriguing. For instance, Mr Bailey originally wrote that the Stabmonk is a relic of the old religion, but this had been toned down to an old religion.

Mr Bayley’s 1996 book Kecks, Keddles & Kesh [5] states that that the plaster model was in fact a copy of an earlier idol which was of the same form as used in worship of Dionysus Sabazios. The classic Greek beer god was popular with the late Roman army and there is evidence that there was a Roman military presence in Chalvey. There were once traces of what was popularly believed to be a wooden fort on Chaddle hill and numerous Roman artefacts have been found nearby. It has been theorised that the cutting of the area’s many early water diversions could have been carried out under the command of retired militarians. If the worship of Sabazios had been introduced to Chalvey by these veterans then it arrived here over a thousand years later than suggested by Witchcraft.

Final thoughts

It is well over half a century since Michael Bayley first proposed the theory that apparently simple story of the slaying of a monkey covered up a deeper and more ancient tradition. No real evidence in support of this has ever come to light. All that exists is conjecture and folklore passed down by word of mouth, which is in general, notoriously unreliable. It would be remarkable if new facts were to ever emerge favouring one scenario or another, but if this does ever happen HCOCV look forward to reporting the details to our readers.

References

- Windsor & Eton Express, 10th June 1865.

- The Chalvey Stab Monk by Michael Bayley. Draft for Berkshire Old and New, No. 9, 1992, published by the Berkshire Local History Association. From the personal collection of local historian Elias Kupfermann.

- The History of Slough by Maxwell Fraser, 1980 edition, Chapter 5: The Manor of Chalvey. Pages 40-45.

- Witchcraft – A hereditary tradition by Jon Dathen, Llanerch Press. 2017, ISBN 9781861431745.

- Kecks, Keddles & Kesh – Celtic Language, Lovespoons and the Cog Almanac. Michael Bayley, 1996, Capall Bann. ISBN 1898307628.

HCOCV gratefully acknowledges the assistance of Elias Kupfermann on this article.

Do you remember the Stabmonk ceremony or can you help us add to our knowledge about it? If so, please get in contact and leave your details with us at HCOCV.

Interesting article. My grandfather who lived in Chalvey until he emigrated in his thirties had a manuscript titled Memoir of a Stabmonk. It was several pages of elegant dip-pen handwriting on faded brown paper sheets which were crumbling at the edges. It must have been written some time in the 19th Century and had previously belonged to his grandfather. I don’t know if he knew the writer W Lovejoy (I think it was) who described details of his life as a Stabmonk. I last saw the memoir in the 1990s when I typed it out but I’ve long since lost my typed copy. I may still have it somewhere on a 5 1/4″ floppy. From what I remember of it, the Stabmonks didn’t seem to be connected with witchcraft or religion but it was more like a close fraternity that had little regard for authority. I’ve put as much as I can remember below but there are probably more than a few misrememberings.

According to the memoir, the public Stabmonk ceremony was a show of bravado that demonstrated to all that the Stabmonks were untouchable. Nothing was said about the origin of the plaster effigy. Despite the public ceremony, the Stabmonks were a secret organisation and locals had to be careful as loose talk could bring punishment. To become a member you had to belong to a Chalvey family and was only open to men. It numbered around 30 members. When Lovejoy came of age he was initiated which involved being cut on the hand and swearing an oath. Stabmonks generally didn’t work for a living in the normal sense and their income mainly came from vice. They profited from brothels in Chalvey which once catered for stagecoach passengers staying at the Salt Hill inns, but although this source had mostly dried up, other lucrative custom came down from Eton and Windsor. Arranging wagered sports such as cock fights and bare knuckle boxing was another source of money. Much of the clientele came from middle and upper classes and the Stabmonks went to great pains to make sure that their customers could come and enjoy the pleasures of Chalvey without fear of being robbed or assaulted. The Stabmonks had their own enforcers consisting of their toughest individuals. They were known as the Black Shadows from their practice of prowling the outer roads at night to catch footpads or others that were threats to their activities. The Black Shadows were usually armed with a cudgel, blade or pistol. They met in a room in Ragstone Road and had a captain who was known by his first name preceded by Black. Lovejoy mentioned that during his youth, the captain was Black Albert. The Black Shadows could be brutal in their enforcement. Local offenders were occasionally found floating face-down in the river Chalve. Undesirable visitors to the village were sometimes left tied to a tree in the marshes. Getting free from their bindings was the least of their worries as a step in the wrong direction could result in sinking into bottomless mud. The captain of the Black Shadows was answerable to the leader of the Stabmonks who was known as the Stabbot. There were some other special ranks but I can’t remember what they were. The Stabmonks had their own way of speaking about their activities and used terms like stealing someone’s shadow and giving the black feather. A stabmonk who became a Black Shadow was said to have taken up the black.

The memoir contained much more detail than I have given. I don’t know what happened to it in the end. After my grandfather passed in the late 1997 it was wasn’t found among his things which is a great shame. Perhaps he lent it or it someone who then lost it or threw it away. If it ever does come to light again I’ll send some scans.

I will relate here that I was summoned to a ceremony on Montem Mound in 2020, due to my aquaintance with local historians, and the ascribed significance of the date. The naming of Ragstone Road, Chalvey in 1964, on my birth certificate seemed to qualify me for some kind of initiation. Being a long term fanatic of celtic historical matters, my patronage of reinactments, making of real chariots and coracles and standing stones, for museum, sculpture parks and use in the real world, this offered up significant interest to me. My legacy on this subject is known to a handful of people, and it is my intention to reclaim the stone sculpture from the dead museum of hidden secrets and breathe life into the stories relayed on this page.

I can further confirm the importance of the involvement of police in the above story and must relay to the reader that an exactly syncronised occurence happened for us in 2020, except the police quickly assumed that we were the “arsing about” and walked off as we continued to fight for the right to get wet in the stream first. Clearly none of the satbmonks known to me are known as criminals, but the celebrations of Dionysus and Sabazio seem very familiar.

I’m an old Chalvey (pronounced ‘charvee’) resident, born just off Church Street on Chaddle Hill. It was known that

a certain Diana ‘D’, who lived in the area, was on pretty good terms with the monks.

I was born in Chalvey Grove in 1948 and my paternal grandparents had lived in Chalvey most of their lives. They met while working on Spackman’s Farm – granddad as a labourer and my nan as a scullery maid. As a child, I was told that anyone born in the Chalvey Grove area had the right to call themselves a stabmonk. We lived in a cottage right at the bottom of Chalvey Grove (no 273) right by the brook and I spent much of my early childhood wandering the fields and playing in the brook.

I wonder if my great uncles son was aware of the stabmonks ?

Ernest Robert Kirtland was born about 1900, in Windsor, Berkshire, the child of Ernest and Annie.

When Ernest Robert Kirtland was born in 1899 in Windsor, Berkshire, his father, Ernest, was 23 and his mother, Annie, was 19.

In May 1921 he was charged for speeding at Barnspool Bridge in Eaton, he was stated to live at Oxford Road, Windsor.

He married Eleanor Alice Dann in 1923 in Eton, Buckinghamshire. They had two children during their marriage. He died on 9 January 1949 in Eton, Buckinghamshire, at the age of 50.

It seems that in 1922 Elanors father who lived in Park Street Slough had something to do with the organisation of soup kitchens

http://www.sloughhistoryonline.org.uk/asset_arena/image/original/sl/ol/sl-ol-slough_observer11021922201704-e-00-000.jpg

When he died in March 1949 in Eton, Buckinghamshire, at the age of 49 his address was 1 Montem lane Chalvey.

Soup Kitchens.. now there’s something from the past! Er..